Texas A&M Law Review Texas A&M Law Review

Volume 9 Issue 2

3-11-2022

If Past is Prologue, then the Future is Bleak: Contracts, Covid–19, If Past is Prologue, then the Future is Bleak: Contracts, Covid–19,

and the Changed Circumstances Doctrines and the Changed Circumstances Doctrines

Danielle K. Hart

Southwestern Law School

, dhart@swlaw.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview

Part of the Contracts Commons, and the Virus Diseases Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Danielle K. Hart,

If Past is Prologue, then the Future is Bleak: Contracts, Covid–19, and the Changed

Circumstances Doctrines

, 9 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 347 (2022).

Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V9.I2.2

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information,

please contact aretteen@law.tamu.edu.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 1 10-AUG-23 12:04

IF PAST IS PROLOGUE, THEN THE FUTURE

IS BLEAK: CONTRACTS, COVID–19, AND THE

CHANGED CIRCUMSTANCES DOCTRINES

by: Danielle Kie Hart*

A

BSTRACT

At the heart of most of the systemic problems currently confronting individ-

uals and businesses as a result of the COVID–19 pandemic is quite literally a

contract. Housing. Insurance. Food. Health care. Child care. Employment.

Manufacturing. Construction. Supply chains. You name it. Contracts are im-

plicated everywhere. So make no mistake: How contract law addresses these

ostensibly private contracts will have profound social consequences. If the past

really is prologue, then the future is indeed bleak. The empirical study con-

ducted for this Article establishes what the conventional wisdom has claimed

for the last 70 years. More specifically, the empirical study here shows that the

common law’s changed circumstances doctrines (“CCDs”)—namely, impossi-

bility, impracticability of performance, and frustration of purpose—will gen-

erally not excuse a party from performing his obligations under a contract,

regardless of the changed circumstance he alleges. Contrary to all the CCD

literature that addresses this issue, this Article makes the unconventional argu-

ment that the CCDs should be more broadly available, meaning they should

be more successful in excusing contract performance when triggered by cata-

strophic circumstances. And unlike the rest of the field, which focuses on the

CCDs themselves, this Article argues that to effectively address the allocation

of unforeseen risks in general and catastrophic risks like a pandemic in partic-

ular, we must reframe the legal approach to contract formation. From there,

given that the solution to the changed circumstances problem preferred by

courts and commentators is an explicit risk-allocation term in the parties’ con-

tract, the solution proposed in this Article to the risk-allocation problem liter-

ally suggests itself. A risk-and-loss-allocation clause should be mandated in

most contracts as a part of contract formation. The type of risk-and-loss-allo-

cation clause and how the clause would work would depend on whether the

contract is co-drafted or adhesive. Generally, the inclusion of a risk-and-loss-

allocation clause would facilitate transactions and encourage contracting by

ensuring that contracts remain efficient and predictable. The main difference

between the risk-and-loss-allocation clause proposed here and existing con-

tract law, of course, is who ends up bearing all the risk and loss occasioned by

the catastrophic changed circumstance. To be clear, if nothing changes and

our approach to contract formation remains the same as it is right now, then

all of the risk and all of the attendant loss will generally be left to lie where it

falls—namely, on the party trying to get out of the contract because of the

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V9.I2.2

* Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School; LL.M. Harvard Law School; J.D.

William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaii; B.A. Whitman College.

My sincere thanks go to Nancy Kim, Stephen Sepinuck, Jay Feinman, and Hila Keren

for reading and commenting on drafts of this Article. Any errors in the text are mine

alone. Southwestern Law School provided generous research support, for which I am

grateful. I also need to thank my research assistants Kimberly Morosi, Ting Yu Lo,

Willow Karfiol, and Andres De La Cruz for their help. Finally, I would like to thank

Meaganne J. Lewellyn, (the Editor-in-Chief), Spencer Lockwood (the Managing Edi-

tor), and all the other editors at the Texas A&M Law Review for their professionalism

and assistance in editing my article. Any errors remaining are my own.

347

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 2 10-AUG-23 12:04

348 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

changed circumstances—and this will be the result regardless of the legal the-

ory used to justify (or demonize) the CCDs or any changes made to the doc-

trines themselves. But if we finally acknowledge the public aspects of contracts

and contract law, namely, that they do in fact produce social consequences

that extend beyond the individual contract and contracting parties, then con-

tracts and contract law may well be part of the solutions to some of the most

pressing problems currently confronting American society now and into the

future.

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

I. I

NTRODUCTION

.......................................... 348

R

II. E

MPIRICAL

S

TUDY OF THE

P

ROBLEM

................... 357

R

A. The Cases ........................................... 361

R

1. Methodology.................................... 362

R

2. The Data and Conclusions ...................... 368

R

B. Some Observations .................................. 373

R

III. S

EARCHING IN

A

LL THE

W

RONG

P

LACES

............... 380

R

IV. P

ROPOSAL

: I

NTERVENING

W

HEN

I

T

M

ATTERS

.......... 392

R

V. C

ONCLUSION

............................................ 402

R

I. I

NTRODUCTION

In December 2019, word first started trickling out about a new virus

in China.

1

By January 20, 2020, the United States reported its first case

of the virus that would later be called COVID–19.

2

By the end of the

month, the World Health Organization declared a global health emer-

gency.

3

And by the end of March 2020, more than half the U.S. popu-

lation was under stay-at-home orders issued by state governors.

4

Not

long after that, reports started pouring in from across the country:

global supply chains were completely upended, leading to disruptions

and shortages;

5

thousands of suppliers across different industries were

devastated as customers cut production or closed shop;

6

businesses

1. See Derrick Bryson Taylor, A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic,

N.Y.

T

IMES

(Mar. 17, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-timeline.html

[https://perma.cc/R6PV-NVHW].

2. Id.

3. Id.

4. See Rosie Perper, Sarah Al-Arshani & Holly Secon, More Than Half of the US

Population Is Now Under Orders to Stay Home—Here’s a List of Coronavirus

Lockdowns in US States and Cities,

B

US

. I

NSIDER

(Mar. 31, 2020, 11:57 PM), https://

www.businessinsider.com/states-cities-shutting-down-bars-restaurants-concerts-cur-

few-2020-3 [https://perma.cc/MNX4-GM6L].

5. Jeff Karoub, Ravi Anupindi: COVID-19 Shocks Food Supply Chain, Spurs

Creativity and Search for Resiliency,

U. M

ICH

. N

EWS

(Apr. 29, 2020), https://

news.umich.edu/covid-19-shocks-food-supply-chain-spurs-creativity-and-search-for-

resiliency/ [https://perma.cc/W8B8-V4BH].

6. Tom Linton & Bindiya Vakil, It’s Up to Manufacturers to Keep Their Suppliers

Afloat,

H

ARV

. B

US

. R

EV

.

(Apr. 14, 2020), https://hbr.org/2020/04/its-up-to-manufac-

turers-to-keep-their-suppliers-afloat [https://perma.cc/XNM5-TBZJ].

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 3 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 349

were failing to pay their rent,

7

closing their stores,

8

and furloughing

their employees;

9

homeowners could not pay their mortgages;

10

rent-

ers could not pay rent, let alone all their other bills;

11

airlines, cruise

ships, and hotels were refusing to issue refunds;

12

and credit card com-

panies and other lenders

13

were contemplating the likelihood of mas-

sive defaults.

14

As of January 10, 2022, there were 60,240,751 confirmed

COVID–19 cases in the United States, and 835,302 Americans lost

their lives because of a virus that has yet to be controlled.

15

Notwith-

standing these mind-boggling and heart-breaking numbers, news out-

lets have been reporting for some time now that the official tallies

significantly undercount the actual number of cases and deaths that

COVID–19 has caused in the United States.

16

7. Jordan Valinsky, Cheesecake Factory Tells Its Landlords It Won’t Be Able to

Pay April Rent,

CNN B

US

.,

https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/26/business/cheesecake-fac-

tory-april-rent-coronavirus/index.html (Mar. 26, 2020, 1:13 PM) [https://perma.cc/

5F5X-CUCY]; see also Konrad Putzier & Esther Fung, Businesses Can’t Pay Rent.

That’s a Threat to the $3 Trillion Commercial Mortgage Market,

W

ALL

S

T

. J.

(Mar. 24,

2020, 8:00 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/businesses-cant-pay-rent-thats-a-threat-

to-the-3-trillion-commercial-mortgage-market-11585051201 [https://perma.cc/D4JY-

5DDD].

8. Jordan Valinsky, Bed Bath & Beyond Is Laying Off 2,800 Employees,

CNN

B

US

.

, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/26/investing/bed-bath-beyond-layoffs (Aug. 26,

2020, 9:07 AM) [https://perma.cc/Y9PR-7M2V].

9. Abha Bhattarai & Rachel Siegel, Macy’s Is Furloughing Most of Its 125,000

Employees Amid Prolonged Coronavirus Shutdown,

W

ASH

. P

OST

(

Mar. 30, 2020),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/30/macys-furloughs-coronavirus/

[https://perma.cc/6RM5-3LQR].

10. Diana Olick, Potential Wave of Mortgage Delinquencies Could Bankrupt the

Payment System

, CNBC

, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/23/coronavirus-us-potential-

wave-of-mortgage-delinquencies-could-bankrupt-payment-system.html (Mar. 23,

2020, 5:28 PM) [https://perma.cc/D4KU-34P6].

11. Eric Morath & Rachel Feintzeig, ‘I Have Bills I Have to Pay.’ Low-Wage

Workers Face Brunt of Coronavirus Crisis,

W

ALL

S

T

. J.

(Mar. 20, 2020, 11:58 AM),

https://www.wsj.com/articles/i-have-bills-i-have-to-pay-low-wage-workers-face-brunt-

of-coronavirus-crisis-11584719927 [https://perma.cc/2NFG-LY78].

12. David Lazarus, Column, No Coronavirus Refund but Credit for a Future

Cruise? Are You Kidding?,

L.A. T

IMES

(Mar. 31, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://

www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-03-31/column-coronavirus-cruise-lines [https://

perma.cc/5FCN-WBUX].

13. W. E. Messamore, The Housing Market Crash’s First Victims Won’t Be Home-

owners,

CCN

, https://www.ccn.com/the-housing-market-crashs-first-victims-wont-be-

homeowners (Sept. 23, 2020, 1:46 PM) [https://perma.cc/QkX2-UZRS].

14. Matt Egan, Credit Card CEO Warns of Dark Times When the $600 Unemploy-

ment Benefit Expires,

CNN B

US

., https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/22/investing/credit-

card-debt-synchrony-unemployment (July 22, 2020, 1:57 PM) [https://perma.cc/M47D-

A656] (Defaults were particularly likely after the forbearance periods granted by the

credit card industry and the $600-a-week unemployment benefits ended.).

15. United States COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Laboratory Testing (NAATs) by

State, Territory, and Jurisdiction,

C

TRS

.

FOR

D

ISEASE

C

ONTROL

& P

REVENTION

,

https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days (Jan. 1, 2021)

[https://perma.cc/8QH7-VCPC].

16. See, e.g., Berkeley Lovelace, Jr., Official U.S. Coronavirus Death Toll Is ‘A

Substantial Undercount’ of Actual Tally, Yale Study Finds,

CNBC,

https://

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 4 10-AUG-23 12:04

350 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

In addition to the mounting death toll and long-term health conse-

quences to survivors, the havoc the COVID–19 pandemic is wreaking

on the American economy is staggering. A few numbers illustrate the

extent of the damage: “The U.S. economy contracted at an annualized

pace of 32.9% in the second quarter [of 2020], . . . the sharpest since at

least the late 1940s.”

17

Economists concluded as early as May 2020

that more than 100,000 small businesses had already closed perma-

nently since the pandemic erupted in March.

18

According to the same

survey, 2% of small businesses were simply gone.

19

The pandemic has

produced the highest unemployment rates in the country since the

Great Depression.

20

More than 50 million Americans were still out of

work at the end of July 2020, and over a million people filed new

unemployment claims every week, except one, since March.

21

As a

result of being laid off, over 5.4 million people lost their health insur-

ance.

22

Further, “[a]t least 11 million renters have fallen behind on

www.cnbc.com/2020/07/01/official-us-coronavirus-death-toll-is-a-substantial-un-

dercount-of-actual-tally-new-yale-study-finds.html (July 2, 2020, 9:11 AM) [https://

perma.cc/D7CE-88SJ]; Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19,

C

TRS

.

FOR

D

ISEASE

C

ONTROL

& P

REVENTION

, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.

htm (Sept. 1, 2021) [https://perma.cc/8EC5-JQ97]; Angela Betsaida B. Laguipo, Offi-

cial U.S. Tallies Likely Undercount COVID-19 Deaths,

N

EWS

M

ED

.

(July 3, 2020),

https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200703/Official-UStallies-likely-undercount-

COVID-19-deaths.aspx [https://perma.cc/X5PJ-LLW7]; Pien Huang, Fauci Says U.S.

Death Toll Is Likely Higher. Other COVID-19 Stats Need Adjusting, Too,

NPR

(May

13, 2020, 12:05 PM), https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/05/13/854873605/

fauci-says-u-s-death-toll-is-likely-higher-other-covid-stats-need-adjusting-too [https://

perma.cc/T5UU-J2CN].

17. William Watts, This ‘Dire’ Economic Situation ‘Deserves To Be Called a De-

pression—A Pandemic Depression’,

M

KT

. W

ATCH

, https://www.marketwatch.com/

story/coronavirus-collapse-is-nothing-less-than-a-depression-a-pandemic-depression-

warn-top-economists-11596728170 (Aug. 6, 2020, 4:07 PM) [https://perma.cc/GJ58-

7NY5].

18. Heather Long, Small Business Used to Define America’s Economy. The Pan-

demic Could Change That Forever,

W

ASH

. P

OST

(May 12, 2020), https://

www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/12/small-business-used-define-americas-

economy-pandemic-could-end-that-forever/ [https://perma.cc/UG7A-YFHQ].

19. Id.

20. Steven Brown, The COVID-19 Crisis Continues to Have Uneven Economic

Impact by Race and Ethnicity,

U

RB

. I

NST

.: U

RB

. W

IRE

(July 1, 2020), https://

www.urban.org/urban-wire/covid-19-crisis-continues-have-uneven-economic-impact-

race-and-ethnicity [https://perma.cc/JE4Z-3T9V].

21. There were more than 1,000,000 unemployment claims for nineteen weeks in a

row. Paul Wiseman, More Than 1 Million Americans File for Unemployment, Again,

A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

(Aug. 27, 2020), https://apnews.com/383eb8856eda415

ed3a3b17894be035f#:~:text=the%20Labor%20Department%20reported%20Thurs-

day,late%20March%2C%20an%20unprecedented%20streak [https://perma.cc/

Y5ZX-A4CS]; Nick Routley, Charts: The Economic Impact of COVID-19 in the U.S.

So Far,

V

ISUAL

C

APITALIST

(July 31, 2020), https://www.visualcapitalist.com/economi

c-impact-of-covid-h1-2020/ [https://perma.cc/565Y-BMBX].

22. Annie Nova, 5.4 Million Americans Have Lost Their Health Insurance. What to

Do If You’re One of Them,

CNBC,

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/14/one-of-the-mil-

lions-of-newly-uninsured-americans-what-to-do-next.html (July 14, 2020, 1:54 PM)

[https://perma.cc/HZM9-TQ58].

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 5 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 351

rent[,] and some 3.6 million households could face evictions in the

coming months.”

23

Notwithstanding the widespread and across-the-board devastation

that COVID–19 is inflicting, it is also agonizingly clear that the pan-

demic’s death toll and economic wreckage disproportionately affects

African Americans, Latinos, and Indigenous communities.

24

People of

color are at increased risk of getting sick and dying from

COVID–19.

25

According to the CDC, as of July 16, 2021, the death

rate for American Indians and Alaskan Natives is 2.4 times higher

than the death rate for whites; for African Americans the death rate is

2.0 times higher, and for Hispanics/Latinx people the death rate is 2.3

times higher.

26

Much of the disparity in these healthcare outcomes is

now widely acknowledged as the result of long-standing systemic

health and social inequality.

27

Moreover, according to the Pew Research Center, 61% of Hispanic

Americans and 44% of Black Americans reported in April 2020 that

either they or someone in their household had lost a job or wages

because of the pandemic, compared to 38% of white adults.

28

The

Center for Budget and Policy Priorities reported that one in five adult

renters were behind on their rent for the week ending July 5, 2021, but

the rates for Black (24%) and Latino (18%) renters were significantly

higher than for white (11%) renters.

29

Black and Hispanic adults were

23. Clifford Colby & Dale Smith, The Federal Eviction Moratorium Is Over. What

Renters Need to Know,

CNET

, https://www.cnet.com/personal-finance/eviction-crisis-

renters-still-have-one-protection-left-until-monday-aug-24/ (Aug. 29, 2021, 9:00 AM)

[https://perma.cc/BU4N-6AEL].

24. Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employ-

ment Hardships,

C

TR

.

ON

B

UDGET

& P

OL

’

Y

P

RIORITIES

, https://www.cbpp.org/re-

search/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-

housing-and (Aug. 9, 2021) [https://perma.cc/RVQ9-N9YP] [hereinafter Tracking the

COVID-19 Recession’s Effects]; Tiffany N. Ford, Sarah Reber & Richard V. Reeves,

Race Gaps in COVID-19 Deaths Are Even Bigger Than They Appear,

B

ROOKINGS

(June 16, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/16/race-gaps-in-

covid-19-deaths-are-even-bigger-than-they-appear/ [https://perma.cc/T997-9HYK].

25. See, e.g., Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority

Groups,

C

TRS

.

FOR

D

ISEASE

C

ONTROL

& P

REVENTION

, https://www.cdc.gov/

coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html (Apr. 19, 2021)

[hereinafter Health Equity Considerations]; Too Many Black Americans Are Dying

from COVID-19,

S

CI

. A

M

. (Aug 1, 2020), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/

too-many-black-americans-are-dying-from-covid-19/ [https://perma.cc/KBT3-V7X2].

26. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity,

C

TRS

.

FOR

D

ISEASE

C

ONTROL

& P

REVENTION

,

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-

ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

(July 16, 2021) [https://perma.cc/MC9G-Q9Y8].

27. See, e.g., Health Equity Considerations, supra note 25; Too Many Black Ameri-

cans Are Dying from COVID-19, supra note 25.

28. Mark Hugo Lopez, Lee Rainie & Abby Budiman, Financial and Health Im-

pacts of COVID-19 Vary Widely by Race and Ethnicity,

P

EW

R

SCH

. C

TR

.

(May 5,

2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/05/financial-and-health-im-

pacts-of-covid-19-vary-widely-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [https://perma.cc/A2QU-LKRJ].

29. Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects, supra note 24.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 6 10-AUG-23 12:04

352 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

also more likely than their white counterparts to say that they could

not pay some of their bills or could only make partial payments in

April.

30

The Urban Institute’s July 2020 research indicated that more

than twice as many Black (37.4%) and Hispanic adults (39.3%) were

food insecure as white adults (17.6%),

31

none of which is surprising

given the employment and wage data.

Clearly, the COVID–19 pandemic’s effects in the United States are

systemic—they affect countless individuals and businesses from every

region of the country, every sector of the economy, and every part of

American society. Systemic effects unquestionably require a systemic

response from the State, with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Eco-

nomic Security (“CARES”) Act

32

being just one example.

But overlooked if not ignored amid this crisis is the role that con-

tracts and contract law play in all this. A contract is quite literally at

the heart of most of the systemic problems currently confronting indi-

viduals and businesses. Housing. Insurance. Food. Health care. Child

care. Employment. Manufacturing. Construction. Supply chains. You

name it. Contracts are implicated everywhere. And given the head-

lines, we all know what is coming down the pike as everyone, individ-

uals and businesses alike, tries to sort through the ruin that

COVID–19 continues to leave in its wake and assess the impact that

the pandemic will ultimately have on their day-to-day existence if not

long-term survival.

Two questions are thus posed by the pandemic for contract law—

both of which this Article addresses. The first question is descriptive:

Does contract law generally provide any relief to people and entities

who find themselves parties to contracts that, when the time set for

performance arrives, look very different from the contracts they origi-

nally entered into? This question specifically triggers an examination

of contract law’s changed circumstances doctrines (“CCDs”)—

namely, impossibility, impracticability of performance, and frustration

of purpose—to predict how contract law will address the particular

“changed circumstance” known as the COVID–19 pandemic. The sec-

ond question is normative: Should contract law make legal relief, like

the CCDs, more broadly available to contracting parties in these kinds

of catastrophic circumstances?

Conventional wisdom and the CCD literature spanning 70 years as-

sume that the CCDs are very limited remedies at best. Practically

speaking, this means that contract law does not provide relief to most

people who want to get out of their contracts because of changed cir-

30. Id.

31. Brown, supra note 20. For 2021 estimates, see Tracking the COVID-19 Reces-

sion’s Effects, supra note 24.

32. CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020) (codified at 15 U.S.C.

§ 9001).

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 7 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 353

cumstances.

33

In a nutshell, this is because the CCDs have front-end

and back-end problems: literally, contract formation and remedy. On

the front end, the CCDs usually fail because they are premised on

assumptions about contracting (i.e., about the parties and the con-

tract-formation process) that simply do not hold up in the real world

today, if they ever did. More specifically, the literature and cases

seemingly agree that the one thing a future adversely affected party

can do to ensure that a CCD will work is to include a provision in the

contract, like a force majeure clause, to protect itself against future

performance-related contingencies.

34

Of course, this solution presup-

poses at a minimum that future adversely affected parties are either

(1) drafting the contracts they are entering into either alone or with

their contracting partners and/or (2) have the wherewithal—knowl-

edge, time, access to information and advice, money, the list goes

on—to not only insist on the inclusion of such a clause in those con-

tracts but also ensure that the clause actually ends up in the written

documents. One or both of these presuppositions does not exist in the

vast majority of consumer or employment contracts, most if not all

online contracts (i.e., like buying music from the Apple store or prod-

ucts from Amazon), or even in a lot of business contracts, particularly

those involving small businesses.

35

Consequently, the absence of an

explicit risk-allocation clause in most contracts should surprise no one.

Yet its absence can be and is used to both indict the party who suppos-

edly could have but nevertheless failed to protect itself and predeter-

mine the outcome of the dispute.

The back-end problem that the CCDs present is that the usual rem-

edy for the CCDs is to excuse the promisor from any further perform-

ance obligation.

36

Excuse, in other words, is either granted or denied.

The remedy is, therefore, presented as a zero-sum game in which one

33. See, e.g., Arthur Anderson, Frustration of Contract—A Rejected Doctrine, 3

D

E

P

AUL

L. R

EV

.

1, 22 (1953); Michael G. Rapsomanikis, Frustration of Contract in

International Trade Law and Comparative Law, 18

D

UQUESNE

L. R

EV

. 551, 558–59

(1980); Steven W. Hubbard, Comment, Relief from Burdensome Long-Term Con-

tracts: Commercial Impracticability, Frustration of Purpose, Mutual Mistake of Fact,

and Equitable Adjustment,

47 M

O

. L. R

EV

.

79, 80 (1982); Leon E. Trakman, Winner

Take Some: Loss Sharing and Commercial Impracticability, 69

M

INN

. L. R

EV

.

471, 477

(1985); Andrew Kull, Mistake, Frustration, and the Windfall Principle of Contract

Remedies, 43

H

ASTINGS

L.J.

1, 1 (1991); Nicholas R. Weiskopf, Frustration of Contrac-

tual Purpose—Doctrine or Myth?, 70

S

T

. J

OHN

’

S

L. R

EV

.

239, 242 (1996); Thomas

Roberts, Commercial Impossibility and Frustration of Purpose: A Critical Analysis, 16

C

AN

. J.L. & J

URIS

.

129, 129 (2003); Willem H. Van Boom, Impossibility, Impractica-

bility and Unforeseen Circumstances 9 (Mar. 25, 2020) (unpublished manuscript)

(available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561025).

34. See infra discussion accompanying notes 196–200.

35. See infra notes 200–08 and accompanying discussion.

36. See, e.g.,

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTRACTS

§ 261 (

A

M

. L. I

NST

.

1981)

(explaining that the “duty to render . . . performance is discharged” if the elements of

impracticability are met).

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 8 10-AUG-23 12:04

354 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

party is usually allocated all of the risk and accompanying losses.

37

Not

surprisingly, in situations where only one party drafted the contract,

the non-drafting party is saddled with all of the risk and loss because

the non-drafting party failed to include a provision protecting itself in

the contract. The reasoning thus becomes not only circular but self-

fulfilling.

While this Article grapples with the CCDs, it diverges from the rest

of the CCD literature in several important ways. To begin with, in-

stead of relying on conventional wisdom or anecdotal evidence about

whether the CCDs are “successful”

38

when raised in practice, this Ar-

ticle is premised on an empirical study. The study reviewed case law

from all federal and state courts in the Seventh and Ninth Circuits.

The findings, detailed below, offer a unique insight. They document

that parties are not generally successful when they raise the CCDs.

That is, courts do not provide any legal relief to the party trying to get

out of the contract because of the changed circumstances in 86% of

the cases in the Seventh Circuit and in 78% of the cases in the Ninth

Circuit.

39

So unfortunately, if the past is indeed a prologue for the

future, then the future looks rather bleak. This is because contract law

will most likely let the risk and loss engendered by the COVID–19

pandemic lie where it falls and leave the contracting parties exactly

where it finds them: namely, in breach of their supply contracts, com-

mercial or residential rental agreements, credit card contracts, etc.

Make no mistake: How contract law addresses these ostensibly pri-

vate contracts will have profound social consequences. How many

people will be evicted from their apartments or lose their homes to

foreclosure? How many of those displaced people will be able to find

new places to live or will remain homeless? How many small busi-

nesses will be forced to shut down, never to reopen? How many em-

ployees will lose their jobs and remain permanently out of the

workforce? How many people will lose their health insurance either

through lost work or because they simply can no longer afford to pay

for their own private insurance? And what will this increase in the

number of medically uninsured do to the long-term health of all these

affected people and to the already existing health care disparities and

exorbitant healthcare costs in general? How many childcare centers

will close permanently, and what will happen to the employment pros-

37. See, e.g., Rapsomanikis, supra note 33, at 557; Trakman, supra note 33, at

482–83; see also infra Table 3 and accompanying discussion.

38. The only reason a contracting party would raise one of the CCDs in arbitration

or litigation would be to excuse that party from having to perform the contract. With

this understanding of the CCDs’ purpose, a CCD would only be “successful” when a

court finds that the party’s performance is excused. See, e.g.,

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTRACTS

§ 261 (

A

M

. L. I

NST

.

1981) (“Where . . . a party’s performance is made

impracticable . . . his duty to render that performance is discharged . . . .”).

39. See infra Table 3 and accompanying discussion.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 9 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 355

pects for many of those parents, particularly women,

40

who need child-

care to work?

41

Obviously, contracts and contract law are not the only explanation

for the existential crises confronting so many Americans and Ameri-

can businesses. In other words, it is not just because so many people

and businesses will end up in breach of their contracts that they find

themselves in uncertain and even dire circumstances. But because all

these breaches of contracts will produce profound social conse-

quences, contracts and contract law are, in fact, an integral part of the

systemic problems currently confronting us all. Consequently, and

contrary to all the CCD literature that addresses this issue,

42

this Arti-

cle makes the unconventional argument that the CCDs should be

more broadly available, meaning they should be more successful in

excusing contract performance when triggered by catastrophic

circumstances.

This Article therefore proposes a novel intervention. Unlike the

rest of the field, which focuses on the CCDs themselves,

43

this Article

argues that to effectively address the allocation of unforeseen risks in

general, and catastrophic risks like a pandemic in particular, we must

reframe the legal approach to contract formation. This is because for-

mation is the core of the entire contract law system;

44

it is literally

where power in a contract is not just embedded but also entrenched.

So, if contract formation is reframed to more accurately reflect con-

tracting in the real world, and given that the solution to the changed

circumstances problem preferred by courts and commentators re-

mains an explicit risk-allocation term in the parties’ contract, then the

solution proposed in this Article to the risk-allocation problem liter-

40. According to the Washington Post, the shuttering of childcare centers may set

women’s employment back an entire generation. See Alicia Sasser Modestino,

Coronavirus Child-Care Crisis Will Set Women Back a Generation,

W

ASH

. P

OST

(July

29, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2020/07/29/childcare-remote-

learning-women-employment/ [https://perma.cc/VZC2-YC8A].

41. Reporting shows that 25% of the 950 preschools and in-home sites surveyed

by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment were closed and that others

that remained open were going into debt to keep their doors open. Edward

Lempinen, California Child Care System Collapsing Under COVID-19, Berkeley Re-

port Says,

B

ERKELEY

N

EWS

(July 22, 2020), https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/07/22/cali-

fornia-child-care-system-collapsing-under-covid-19-berkeley-report-says/ [https://

perma.cc/ZW33-PEZG].

42. See infra discussion accompanying notes 190–95.

43. See, e.g., Hubbard, supra note 33, at 104–05 (urging equitable price adjustment

as the solution); Trakman, supra note 33, at 481–82, 484–85 (arguing that loss sharing

would minimize many of the issues currently plaguing CCDs in theory and in applica-

tion); Kull, supra note 33, at 6 (articulating the windfall principle, which argues that

since the parties have not allocated the risk between them, the losses should be left to

lie where they fall).

44. See generally Danielle Kie Hart, Contract Formation and the Entrenchment of

Power, 41

L

OY

. U. C

HI

. L.J.

275 (2009) [hereinafter Hart, Formation] (arguing that

the power of contracts comes from their formation, particularly the element of mutual

assent); see also infra Part IV.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 10 10-AUG-23 12:04

356 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

ally suggests itself: A risk-allocation clause should be included in most

contracts as part of contract formation. More bluntly, the specific so-

lution will depend on the type of contract involved: (1) For co-drafted

contracts, it would require the inclusion of a standard, negotiable, and

variable risk-and-loss-allocation clause and a good-faith-negotiation

provision; and (2) for most adhesion contracts, it would require the

inclusion of a standard, nonnegotiable, and non-variable risk-and-loss

allocation clause and a good faith negotiation provision. Another im-

portant and innovative contribution of this paper, therefore, is that

this Article explicitly recognizes two types of contracts—co-drafted

and adhesive—and proposes a specific solution based on the type of

contract at issue.

In particular, including a risk-and-loss-allocation clause would facil-

itate transactions and encourage contracting in general by ensuring

that contracts remain efficient and predictable. The risk-and-loss-allo-

cation clause would let contracting parties know in advance how risks

and losses would be allocated between them if a catastrophic changed

circumstance occurs in the future, thereby increasing trust between

the parties and enabling the parties to plan their present and future

affairs accordingly. This is because the risk-and-loss-allocation clause

would require courts and other dispute resolution decision-makers to

shift all the risk and all the loss onto the drafting party in contracts

where only one party actually drafted the contract or onto the party

designated in a co-drafted contract scenario. Because risk and loss

would be explicitly and intentionally allocated in the contract, the

CCDs should arguably not even be necessary. The contract itself

would predetermine the outcome. That said, should the contracting

party that is unhappy with the contract’s risk-and-loss-allocations pur-

sue a contract claim in court (or through arbitration), the existence of

a risk-and-loss-allocation clause would predetermine the outcome of

the CCD cases just as the absence of a risk-and-loss-allocation clause

does now. In such cases, the CCDs would and should be more broadly

available to excuse performance under a contract.

The main difference between the risk-and-loss-allocation clause

proposed here and existing contract law, of course, is who bears all the

risk and loss occasioned by the catastrophic changed circumstance. So

to be clear, if nothing changes and our approach to contract formation

remains the same as it is right now, then all the risk and all the attend-

ant loss will generally be left to lie where it falls, namely, on the party

trying to get out of the contract because of the changed circumstances.

This will be result regardless of the legal theory used to justify (or

demonize) the CCDs or any changes made to the doctrines

themselves.

One of this Article’s most important contributions, therefore, is to

expose the social consequences created when the effects of ostensibly

private contracts between private parties, particularly adhesion con-

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 11 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 357

tracts (i.e., where only one party drafts the document), are aggregated.

Of course, even if the solution suggested in this Article gets adopted,

it will come too late to help any of the people and businesses affected

by the COVID–19 pandemic. The risk-and-loss-allocation clause and

good-faith-negotiation provision being proposed here simply do not

exist in any of these affected contracts. For this reason, this Article

also proposes a principled way for judges or arbitrators deciding CCD

cases going forward, particularly cases involving adhesion contracts, to

find that the risk and loss created by a catastrophic changed circum-

stance should fall on the drafting party.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that any relief provided to a

contracting party under the CCDs via any of the solutions proposed in

this Article would be meted out contract by contract. Because of this

case-by-case approach, contract law is not and never will be a systemic

fix for systemic failures in American society. Systemic relief must

come from the State. That said, the United States is at a critical mo-

ment in its history right now, and as a result, contract law is or will be

forced to confront a critical moment in its evolution. If we finally ac-

knowledge the public aspects of contracts and contract law—namely,

that they do in fact produce social consequences that extend beyond

the individual contract and contracting parties—then contracts and

contract law may well be part of the solutions to some of the most

pressing problems confronting American society now and into the

future.

The Article proceeds as follows: Part II begins with a primer on the

CCDs and then lays out the methodology, findings, and analysis of the

empirical study conducted for the Article. The primary conclusion

from the study is that the CCDs are not generally successful when

raised in practice, even when the contingency causing the contractual

disruption was the September 11th terrorist attacks, the Great Reces-

sion of 2007–2009, or other similarly catastrophic events. Part III then

highlights the distinction between co-drafted contracts and adhesion

contracts and examines in more detail why courts and commentators

are so reluctant to let people out of their contracts under the CCDs.

The focus on contract formation as the source of the problem distin-

guishes this Article from the rest of the CCD literature and introduces

some Legal Realism into both the discussion and the explanation. Fi-

nally, Part IV discusses the solutions proposed by this Article in detail,

specifically how the risk-and-loss-allocation clause and the good-faith-

negotiation provision would work in both a co-drafted contract and an

adhesive contract scenario.

II. E

MPIRICAL

S

TUDY OF THE

P

ROBLEM

Before discussing the data, a primer on the CCDs is needed. The

CCDs typically include impossibility of performance, impracticability

of performance (a.k.a. commercial impracticability), and frustration of

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 12 10-AUG-23 12:04

358 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

purpose (a.k.a. commercial frustration).

45

All the CCDs are triggered

by changed circumstances, that is, when circumstances change so dra-

matically after contract formation such that performance is (1) literally

impossible, (2) impracticable because of excessive and unreasonable

cost, or (3) almost completely valueless to one party.

46

While CCDs

have changed circumstances in common, they differ from each other

in specific ways, including how they address different performance-

related problems and receive separate analytical treatment.

47

The doctrine of impossibility requires objective impossibility. In

other words, the party seeking to get out of the contract must prove

that the performance promised in the contract is physically not possi-

ble, that is, that no one could perform.

48

The Taylor v. Caldwell case is

the oft-cited example.

49

In Taylor, the parties contracted for Taylor to use Caldwell’s music

hall for a series of performances that would occur over four days.

50

Unfortunately, an accidental fire destroyed Caldwell’s music hall

before the first performance was scheduled to take place.

51

The de-

struction of the music hall made Caldwell’s duty to provide that music

hall objectively impossible.

52

Taylor then sued Caldwell for breach of

contract.

53

The Court held that Caldwell’s duty to provide the music

hall under the parties’ contract was excused because it found that the

parties contracted on the basis of the continued existence of the music

hall.

54

Contract law theoretically shifted from impossibility to impractica-

bility of performance sometime in the 1900s.

55

Or perhaps it is more

accurate to say that contract law acknowledged something it already

recognized: Literal impossibility was not required to excuse perform-

ance.

56

Instead, the party seeking relief from a contract could now

45. See Rapsomanikis, supra note 33, at 551.

46. See id.

47. Richard A. Posner & Andrew M. Rosenfield, Impossibility and Related Doc-

trines in Contract Law: An Economic Analysis, 6

J. L

EGAL

S

TUDS

.

83, 85 (1977).

48. See id.; Uri Benoliel, The Impossibility Doctrine in Commercial Contracts: An

Empirical Analysis, 85

B

ROOK

. L. R

EV

.

393, 395–96 (2020).

49.

E. A

LLAN

F

ARNSWORTH

, C

ONTRACTS

§ 9.5 (

4th ed

. 2004) (

discussing Taylor v.

Caldwell, (1863) 122 Eng. Rep. 309 (QB), and calling it “the fountainhead of the

modern law of impossibility”).

50. Taylor, 122 Eng. Rep. at 312.

51. Id.

52. Id.

53. Id. at 310.

54. Id. at 314–15.

55. See, e.g., Hubbard, supra note 33, at 84; Liu Chengwei, Remedies for Non-

performance: Perspectives from CISG, UNIDROIT Principles & PECL § 19.3.1

(2003) (unpublished manuscript) (available at https://www.academia.edu/37883872/

Remedies_for_Non_performance_Perspectives_from_CISG_UNIDROIT_Principles_

and_PECL).

56. See, e.g.,

F

ARNSWORTH

, supra note 49, § 9.6 (“[C]ourts did not insist on strict

impossibility even under the traditional analysis.”). But see

J

EFF

F

ERRIELL

, U

NDER-

STANDING

C

ONTRACTS

572 (3rd ed. 2014).

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 13 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 359

show that the performance had become “impracticable,” meaning that

it could be done only with extreme and unanticipated difficulty or

cost.

57

With impracticability of performance, therefore, the perform-

ance is not literally impossible, it has just become too difficult or costly

to perform.

58

The modern doctrine of impracticability of performance

originated in the Mineral Park Land Co. v. Howard case.

59

In Mineral Park, a contractor agreed to remove all the gravel from

the owner’s land that the contractor required for a construction pro-

ject and purchase it at a fixed price.

60

The contractor ended up taking

only some of the gravel needed for the construction project from the

owner’s land because, as the parties discovered after extraction began,

much of the gravel on the owner’s land was submerged underwater.

61

The contractor therefore argued that its performance should be ex-

cused because removing the gravel that was submerged required a dif-

ferent method of extraction and would cost 10 to 12 times more to

remove.

62

The California Supreme Court agreed that the extreme in-

crease in cost justified the contractor’s nonperformance. According to

the court, “[a] thing is impossible in legal contemplation when it is not

practicable; and a thing is impracticable when it can only be done at

an excessive and unreasonable cost.”

63

Finally, the frustration of purpose doctrine generally deals with

changed circumstances that make the contract almost completely

worthless to one of the parties.

64

So like impracticability of perform-

ance, performance of the contract is not literally impossible. Rather,

performance is still possible. But frustration of purpose differs from

impracticability of performance because the adversely affected party

must be able to show that its principal purpose in entering into the

contract has been frustrated.

65

More importantly, that purpose is frus-

trated only where the object is “so completely the basis of the contract

that, as both parties know, without it the contract would have little

meaning.”

66

In other words, frustration of purpose requires that both

parties have some kind of common understanding about the principal

purpose of the contract. The Krell v. Henry

67

case is the usual

example.

57. See Hubbard, supra note 33, at 84; Liu, supra note 55, § 19.3.1.

58. Posner & Rosenfield, supra note 47, at 86; Benoliel, supra note 48, at 397.

59.

F

ERRIELL

, supra note 56, at 572 (discussing Min. Park Land Co. v. Howard,

156 P. 458 (Cal. 1916)).

60. Min. Park, 156 P. at 458.

61. Id. at 458–59.

62. Id. at 459.

63. Id. at 460.

64.

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTS

.

§ 265 cmt. a (

A

M

. L. I

NST

.

1981); Hub-

bard, supra note 33, at 83, 93; Anderson, supra note 33, at 4; Weiskopf, supra note 33,

at 239–40.

65. Weiskopf, supra note 33, at 240.

66. Id. at 248 (quoting

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTS

.

§ 265 cmt. a).

67. Krell v. Henry [1903], 2 KB 740.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 14 10-AUG-23 12:04

360 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

In Krell, the defendant rented a room from the plaintiff that over-

looked the route of the coronation procession for King Edward VII.

68

The plaintiff was aware that the defendant’s primary purpose for rent-

ing the room was to view the coronation procession because the plain-

tiff had advertised his room specifically for this purpose.

69

When the

procession did not take place as originally scheduled, the defendant

no longer had any need of the room and refused to pay the balance

due under the contract.

70

The court held that the coronation proces-

sion was “the foundation of the contract” and was recognized as such

by both parties.

71

As a result, and even though the defendant’s prom-

ise to pay was obviously still performable, the court held that the can-

cellation of the coronation procession excused the defendant from his

duty to pay.

72

As the foregoing discussion shows, the CCDs have been around for

a long time.

73

Consequently, considerable conventional wisdom has

developed about them. Some of that wisdom includes the following:

(1) impossibility and impracticability of performance are generally

raised by the contracting party with performance obligations, like

building the house, delivering the goods, etc., as opposed to the paying

party;

74

(2) contract law shifted away from impossibility to impractica-

bility;

75

(3) frustration of purpose is generally raised by the paying

party;

76

(4) courts are much more reluctant to excuse performance

based on frustration of purpose;

77

and (5) the changed circumstance

(i.e., the event) that triggers the CCDs (a) will usually involve “acts of

God” or acts by third parties

78

and (b) cannot be in the control of the

68. Id. at 740.

69. Id. at 750.

70. Id. at 740.

71. Id. at 754.

72. Id.

73. The dates associated with the aforementioned decisions are illustrative. Taylor

v. Caldwell, (1863) 122 Eng. Rep. 309 (QB) (impossibility); Min. Park Land Co. v.

Howard, 156 P. 458 (Cal. 1916) (impracticability); Krell, 2 KB at 740 (frustration of

purpose); see also Rapsomanikis, supra note 33, at 551.

74. See, e.g.,

F

ARNSWORTH

, supra note 49, § 9.7.

75. The Restatement (Second) of Contracts, for example, only discusses changed

circumstances in terms of impracticability, not impossibility. See, e.g.,

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTS

.

§§ 261–64 (

A

M

. L. I

NST

. 1981); see also,

F

ERRIELL

, supra note

56, at 569 (“Contract law originally limited this escape to situations in which the

change of circumstances had made performance literally impossible . . . . The law later

expanded to provide relief where performance had not become completely impossi-

ble, but where . . . the burden of performing had changed in a way that was beyond

the risks assumed by the parties when the contract was made[, i.e.,] performance . . .

ha[d] become ‘commercially impracticable.’”);

F

ARNSWORTH

, supra note 49, § 9.6 (re-

ferring to impracticability as the new synthesis of the law of impossibility).

76. See, e.g.,

F

ARNSWORTH

, supra note 49, § 9.7.

77. See id.; Weiskopf, supra note 33, at 267; Van Boom, supra note 33, at 9.

78. For example, all the illustrations used in Restatement (Second) of Conts.

§§ 261 and 265 involve acts of God or acts by third parties. See, e.g.,

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTS

.

§ 261 cmt d. (“Events that come within the rule stated in this

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 15 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 361

party seeking to excuse its performance.

79

But if the changed circum-

stance preventing the party seeking to be excused from performing

was caused by the other party, then this should ordinarily be treated

as a breach of contract by the other party.

80

This last piece of conven-

tional wisdom therefore suggests that if the other party’s actions that

caused the changed circumstances was not a breach by that party, then

the party seeking to be excused should be able to argue one of the

CCDs to justify its non-performance. It just remains to be seen

whether the conventional wisdom about the CCDs holds true in

practice.

A. The Cases

Once in a contract, it is very difficult to get out.

81

This generally

accepted proposition has been substantiated with more and more em-

pirical work,

82

most notably with respect to the doctrine of unconscio-

nability.

83

But not a lot of empirical work exists that examines the

CCDs. Notably, only a couple of such studies examine the CCDs

under U.S. law.

84

Thus, by focusing on the CCDs, this Subsection adds

to the growing body of empirical scholarship, confirming that courts

rarely let parties out of a contract once that contract has been formed.

Section [impracticability] are generally due either to “acts of God” or to act of third

parties.”)

79. With respect to the changed circumstance outside the control of the party

seeking to be excused, see, e.g., Restatement (Second) of Conts. § 261 (“Where, after

a contract is made, a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault

. . . .”); id. § 265 (“Where, after a contract is made, a party’s principal purpose is

substantially frustrated without his fault . . . .”).

80. See, e.g.,

R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

C

ONTS

.

§ 261 cmt d. (“If the event that

prevents the obligor’s performance is caused by the obligee, it will ordinarily amount

to a breach by the latter . . . without regard to this Section.”).

81. See generally, Danielle Kie Hart, In & Out—Contract Doctrines in Action, 66

H

ASTINGS

L.J.

1661 (2015) [hereinafter, Hart, In & Out]; see also Robert M. Lloyd,

Making Contracts Relevant: Thirteen Lessons for the First-Year Contracts Course, 36

A

RIZ

. S

T

. L.J.

257, 267 (2004); Blake D. Morant, The Teachings of Dr. Martin Luther

King, Jr. and Contract Theory: An Intriguing Comparison, 50

A

LA

. L. R

EV

.

63, 110

(1998); Robert A. Hillman, Contract Excuse and Bankruptcy Discharge, 43

S

TAN

. L.

R

EV

.

99, 99 (1990) (“Notwithstanding academic writing that reports or urges expan-

sion of the grounds of excuse, courts actually remain extremely reluctant to release

parties from their obligations.”).

82. See, e.g., Hart, In & Out, supra note 81 (evaluating duress, modification, and

impracticability of performance empirically through various cases); Grace M. Giesel,

A Realistic Proposal for the Contract Duress Doctrine, 107

W. V

A

. L. R

EV

.

443,

463–65 (2005) (exploring courts’ treatment of duress in contract disputes).

83. See Brian M. McCall, Demystifying Unconscionability: A Historical and Em-

pirical Analysis, 65

V

ILL

. L. R

EV

. 773 (2020) (performing an empirical study of uncon-

scionability and summarizing other existing empirical studies covering the same

doctrine).

84. See Benoliel, supra note 48; Anderson, supra note 33. There are, however,

empirical studies that examine CCDs in other countries. See, e.g., Smaran Shetty &

Pranav Budihal, Force Majeure, Frustration and Impossibility: A Qualitative Empirical

Analysis (Aug. 6, 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3665213 [https://perma.cc/47AM-

MU9J] (Indian law).

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 16 10-AUG-23 12:04

362 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

I first describe the methodology used to collect the cases for the Arti-

cle. Then, I present the results of the data collected and draw some

conclusions based on that data. To conclude the Subsection, I make

some observations based on the data, including, but not limited to,

some comments about the conventional wisdom discussed in the CCD

primer above.

1. Methodology

The case law empirical study conducted here focused on three com-

mon law doctrines: impossibility of performance, supervening imprac-

ticability of performance, and supervening frustration of purpose.

Excluded were existing and temporary impracticability or frustration.

This study updates earlier impracticability of performance research I

conducted in 2015

85

by adding five and a half years of additional data

(2014–2019). The study is entirely new with respect to impossibility

and frustration of purpose. All told, the study includes 20 years of

data for impossibility and impracticability of performance

(2000–2019)

86

and ten years of data for frustration of purpose

(2005–2015). This ten-year window for frustration of purpose was spe-

cifically selected to capture the jurisprudential outcomes surrounding

the Great Recession (2007–2009). A total of 136 cases from the fed-

eral and state courts within the Seventh and Ninth Circuits were col-

lected for the study.

87

The research was conducted in the following

steps:

I. Selecting the Jurisdictions. The Seventh and Ninth Circuits

were selected, because these circuits were the ones used in my

2015 empirical study.

88

That said, the reasons these circuits were

selected for the previous study make sense here as well. More

specifically, the Ninth Circuit was selected because, with nine

states,

89

it is the largest of all thirteen circuits and is likely to

hear a lot of cases. The Ninth Circuit also has a reputation of

85. Hart, In & Out, supra note 81.

86. Even though impossibility is entirely new in this empirical study, I used the

same time period for impossibility that I used for impracticability of performance

(2000–2019). This is because impossibility and impracticability of performance are

similar enough doctrines that using a different time frame would seemingly skew the

data.

87. The cases collected here are from a dataset of cases consisting of court opin-

ions made available on LexisNexis. Consequently, the following are omitted from the

available LexisNexis dataset: (1) all cases where the parties voluntarily agreed to can-

cel the contract (either because no lawsuit was ever brought or the case was settled

before a decision) and (2) an unknowable number of cases litigated in state court that

were not appealed since very few state trial court decisions result in an opinion.

88. Hart, In & Out, supra note 81.

89. The states within the Ninth Circuit are Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii,

Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. What Is the Ninth Circuit?, https:/

/www.ca9.uscourts.gov/judicial-council/what-is-the-ninth-circuit/ [https://perma.cc/

CFF9-9U3U].

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 17 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 363

being more consumer friendly, suggesting that courts there

might be more inclined to excuse people from their contractual

obligations than courts in other circuits. The Seventh Circuit, in

contrast, is much smaller, encompassing only three states,

90

but

it is closely associated with the Law and Economics approach

and therefore has a reputation for being less consumer friendly,

suggesting that courts there might be more likely to require that

people fulfill their contractual promises.

91

II. The Searches. Each search was conducted on LexisNexis for

Law School. The searches were broken down by doctrine, ap-

plying the timelines, jurisdictional filters, and search terms

specified below:

a. Jurisdictional Filters—All Searches

i. Seventh Circuit—Jurisdiction: Seventh Circuit, Illinois,

Indiana Wisconsin

ii. Ninth Circuit—Jurisdiction: Ninth Circuit, Alaska, Ar-

izona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada,

Oregon, Washington

* All the federal and state courts in the Seventh

and Ninth Circuits are included in the jurisdic-

tional filters.

b. Impracticability of Performance: Original Search (from

2015 Study)

i. Timeline: January 1, 2000, through March 1, 2014

ii. Search Terms

1. Impracticability of Performance: (impract! near/25

perform!) and (perform! near /25 contract).

c. Impracticability of Performance: Updated Search (2020)

i. Timeline: March 15, 2014, through December 31, 2019

ii. Search Terms

1. impract! near/25 perform!

2. perform! near /25 contract

3. (impract! near/25 perform!) and (perform! near /25

contract)

4. “impracticability of performance”

5. “Restatement (Second) of Contracts §261”

d. Impossibility of Performance

i. Timeline: January 1, 2000, through December 31, 2019

ii. Search Terms

1. “Impossibility of Performance”

e. Frustration of Purpose

i. Timeline: January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2015

90. The states within the Seventh Circuit are Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin.

About the Court, https://www.ca7.uscourts.gov/about-court/about-court.htm [https://

perma.cc/XHK8-Z56V].

91. See Hart, In & Out, supra note 81, at 1668.

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 18 10-AUG-23 12:04

364 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

ii. Search Terms

1. “Frustration of purpose”

2. “Restatement (Second) of Contracts §265”

III. Screening the Cases. The searches conducted for this study

pulled up 176 cases for the Seventh Circuit and 502 cases for

the Ninth Circuit.

92

Each case was initially screened to ensure

that it addressed the relevant doctrine being examined and

that some part of the case was decided based on that doctrine.

Only cases that satisfied these criteria were selected for sub-

stantive review.

IV. Substantive Review of the Cases. Each of the selected cases

was then read to ensure, first, that it fell within the jurisdiction

of the Seventh and Ninth Circuits and, second, that it did in

fact address and decide the contract law doctrine at issue.

Cases were omitted, for example, when the court deciding it

applied law from a state outside of the two circuits that were

the subject of this study (i.e., an Illinois court applying New

Jersey law).

93

On occasion, substantive review revealed that

the case decided an issue involving more than one doctrine,

for example, both impossibility and frustration of purpose. In

this situation, the case was selected for both doctrines. It also

happened occasionally that a case being reviewed for one doc-

trine, for example frustration of purpose, actually focused

more on another doctrine, like impracticability of perform-

ance. In these situations, the case was included as a selected

case for the other doctrine even though the case did not ap-

pear in the search conducted for that doctrine.

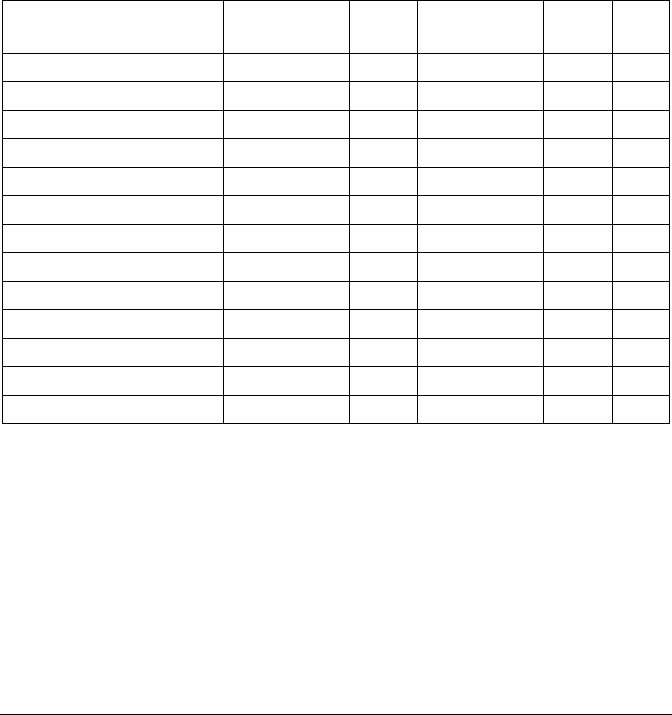

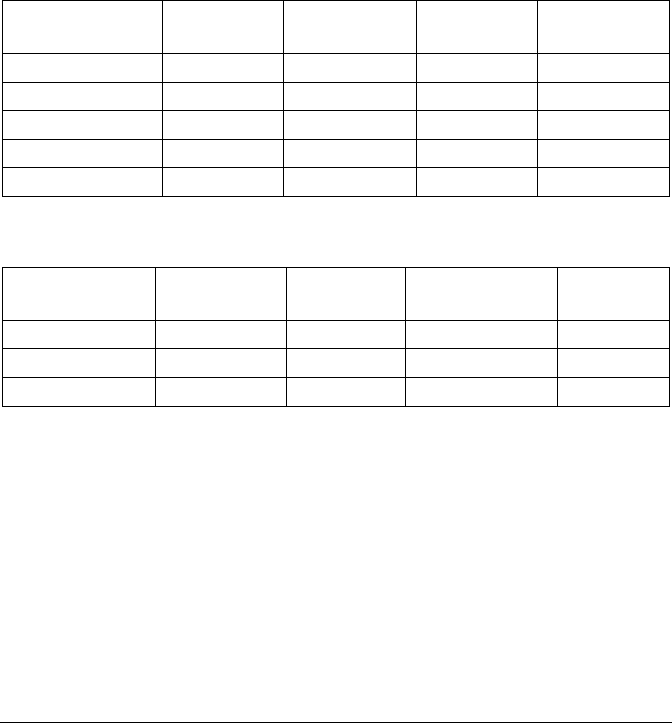

V. Totals. At the end of the substantive review process, a total of

136 cases were captured—37 cases for the Seventh Circuit and

99 cases for the Ninth Circuit. Table 1 provides a summary of

the captured cases in each circuit by substantive category and

doctrine.

92. The original empirical study I published in 2015 did not separate the number

of cases by doctrine. The study only included the total number of cases found for all

doctrines examined in the earlier project, so the numbers stated in this text only re-

flect the cases discovered in the searches conducted for this empirical study.

93. See, e.g., Days Inn of Am., Inc. v. Patel, 88 F. Supp. 2d 928 (C.D. Ill. 2000)

(applying New Jersey law).

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 19 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 365

T

ABLE

1: S

UMMARY OF

C

APTURED

C

ASES BY

S

UBSTANTIVE

C

ATEGORY

94

Claim Category 7

th

Cir:

Performance

7

th

Cir:

FoP

9

th

Cir:

Performance

9

th

Cir:

FoP

Total

Real Property 7 1 31 20 59

Employment 3 2 5 3 13

Goods 4 3 3 2 12

Misc. Commercial 3 1 4 2 10

Settlement Agreements 2 2 4 1 9

Misc. Services 3 0 5 0 8

Family 0 0 4 2 6

Insurance 1 1 2 2 6

Public Util./Energy 1 0 1 2 4

Construction 1 0 3 0 4

Education 0 0 2 0 2

Leases 2 0 0 0 2

Software 0 0 1 0 1

The vast majority of the contracts in the captured cases appear to be

commercial (as opposed to consumer) contracts between commercial

parties.

95

I say, “appear to be,” because none of the cases actually

included a copy of the contracts involved in the disputes or provide

many details about the parties. So determining what kind of contracts

were involved in each case is based on who the contracting parties are

(i.e., individuals, government entities, or businesses) and the subject

matter of the contract (i.e., construction, business, etc.). Based on

these loose parameters, only 38 non-business transactions exist out of

the 136 cases collected for the empirical study.

96

Out of those 38 cases,

94. See Appendix 1 for a list of all captured cases by circuit and doctrine (the

performance doctrine, which combines impossibility and impracticability, and the

doctrine of frustration of purpose (“FoP”)) (on file with Author). Settlement

agreements included commercial settlements, indemnity agreements, and consent

decrees. The “Family” category includes all family-related settlement agreements.

95. A “commercial contract” is defined broadly here as one that involves any kind

of business and/or is economic in nature. Hence, a “commercial party” is a party (in-

dividual or business entity) that enters the contract for profit or economic reasons, as

opposed to a “consumer,” which is specifically defined by the U.C.C. as “an individual

who enters a transaction primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.”

U.C.C. § 1-201(b)(11) (

A

M

. L. I

NST

. & U

NIF

. L. C

OMM

’

N

2020) (consumer).

96. The cases involving non-business transactions, grouped by type, are as follows:

R

ESIDENTIAL

R

EAL

P

ROPERTY

T

RANSACTIONS

(17):

Prospect Enters. v. Ruff, No. 10-1026, 2011 WL 2683004, at *2–3 (C.D. Ill. July 11,

2011) (sale of townhome); Exec. Prop. Mgmt., Inc. v. Watson, No. 1-10-1890, 2011 WL

10069467, at *1 (Ill. App. Ct. Mar. 29, 2011) (residential lease); Ury v. Di Bari, No. 1-

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 20 10-AUG-23 12:04

366 TEXAS A&M LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9

15-0277, 2016 WL 2610167, at *1 (Ill. App. Ct. May 5, 2016) (sale of condo); Samuels

v. Merrill, No. B190158, 2007 WL 2084093, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. July 23, 2007) (sale of

condo); Miranda v. Williams, No. F054365, 2008 WL 4636445, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App.

Oct. 21, 2008) (purchase and construction of residential property); Archundia v.

Chase Home Fin. LLC, No. 09-CV-00960 (AJB), 2009 WL 1796295, at *1 (S.D. Cal.

June 23, 2009) (residential property foreclosure); Bean v. BAC Home Loans Servic-

ing, LP, No. 11-CV-553, 2012 WL 10349, at *1 (D. Ariz. Jan. 3, 2012) (residential

property foreclosure); Reader v. BAC Home Loan Servicing LP, No. 11-CV-553, 2012

WL 125977, at *1 (D. Ariz. Jan. 17, 2012) (residential property foreclosure); Gutierrez

v. PNC Mortg., No. 10CV01770, 2012 WL 1033063, at *1 (S.D. Cal. Mar. 26, 2012)

(home loan refinance and modification); Wear v. Sierra Pac. Mortg. Co., No. C13-535,

2013 WL 6008498, at *1 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 12, 2013) (residential home mortgage fore-

closure); Deschaine v. IndyMac Mortg. Servs., No. CIV. 2:13-1991, 2013 WL 6054456,

at *1–2 (E.D. Cal. Nov. 15, 2013) (residential home mortgage); Lane v. Cooper, No.

D062806, 2014 WL 606556, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Feb. 18, 2014) (condo CC & Rs); Bob

Spain Real Est. Servs., Inc. v. Cox, No. 32006-5, 2015 WL 422371, at *1 (Jan. 27, 2015)

(real estate listing agreement); Tanner v. Keating, No. F071491, 2017 WL 2376393, at

*1 (Cal. Ct. App. June 1, 2017) (purchase of residence); Balboa Bay Club, Inc. v.

Howard, No. G033413, 2005 WL 827064, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Apr. 11, 2005) (residen-

tial lease); Goldberg v. Prickett, No. B203934, 2009 WL 179572, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App.

Jan. 27, 2009) (sale of residential leasehold); Lohman v. Ephraim, No. B207755, 2010

WL 6901, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Dec. 30, 2009) (sale of residential property).

E

MPLOYMENT

-R

ELATED

T

RANSACTIONS

(8):

Dalkilic v. Titan Corp., 516 F. Supp. 2d 1177, 1181 (S.D. Cal. 2007); Caravette v. Z

Trim Holdings, Inc., No. 2-11-0087, 2011 WL 10457470, at *1 (Ill. App. Ct. Sept. 29,

2011); Downs v. Rosenthal Collins Grp., LLC, 963 N.E.2d 282, 286, 288 (Ill. App. Ct.

2011); Ryan v. Estate of Sheppard (In re Estate of Sheppard), 789 N.W.2d 616, 617

(Wis. Ct. App. 2010); Dauod v. Ameriprise Fin. Servs., No. SACV 10-00302, 2010 WL

11595801, at *1 (C.D. Cal. July 29, 2010); LECG, LLC v. Unni, No. C-13-0639, 2014

WL 2186734, at *1 (N.D. Cal. May 23, 2014); Kische USA LLC v. Simsek, No. C16-

0168, 2017 WL 3895545, at *1–2 (W.D. Wash. Sept. 6, 2017); Mitchell v. Leed HR,

LLC, No. 2:14-CV-00026, 2015 WL 1611447, at *1–2 (D. Idaho Apr. 10, 2015).

F

AMILY

-R

ELATED

T

RANSACTIONS

(5):

Archer v. Archer (In re Marriage of Archer), No. 1 CA-CV 08-0543, 2009 WL

1682146, at ¶ 2 (Ariz. Ct. App. June 16, 2009) (marriage settlement agreement); In re

Marriage of Weber, No. 64739-3, 2011 WL 1947728, at *1 (Wash. Ct. App. May 23,

2011) (marital asset agreement); Hibbard v. Hibbard (In re Marriage of Hibbard), 151

Cal. Rptr. 3d 553, 554 (Ct. App. Jan. 15, 2013); Bennett v. Foss, No. A137452, 2014

WL 1679559, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Apr. 29, 2014) (settlement memo); Klein v. Klein,

No. B213125, 2009 WL 3807442, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Nov. 16, 2009) (marital settle-

ment agreement).

M

ISCELLANEOUS

T

RANSACTIONS

(8):

Tahir v. Imp. Acquisition Motors, LLC, No. 09 C 6471, 2014 WL 985351, at *1 (N.D.

Ill. Mar. 13, 2014) (sale of a car); Ploegman v. Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry., Co., No.

46776, 2002 WL 1161387, at *1 (Wash. Ct. App. June 3, 2002) (personal injury indem-

nity agreement); Carsh v. Chaparral Pines, LLC, No. 2 CA-CV 2002-0175, 2003 Ariz.

App. Unpub. LEXIS 59, at *2–3 (Ct. App. Aug. 4, 2003) (contract involving a golf

membership); Kashmiri v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 67 Cal. Rptr. 3d 635, 638–39

(Ct. App. Nov. 2, 2007) (contract regarding cost of education); Babcock v. ING Life

Ins. & Annuity Co., No. 12-CV-5093, 2013 WL 24372, at *1–2 (E.D. Wash. Jan. 2,

2013) (insurance structured settlement); Achziger v. IDS Prop. Cas. Ins., No. C14-

\\jciprod01\productn\T\TWL\9-2\TWL203.txt unknown Seq: 21 10-AUG-23 12:04

2022] IF PAST IS PROLOGUE 367

only 15 of them appear to involve adhesive contracts,

97

i.e., contracts

drafted by one party, usually but not always on a standard form, and

presented to the other party on a take it or leave it basis.

98

Four com-

mercial contracts could also be characterized as adhesive.

99

To be clear: I do not claim that the empirical study conducted for

this Article captured all the CCD cases in the Seventh and Ninth Cir-

cuits. For example, this study focused exclusively on the common law

CCDs and not the sale of goods under the Uniform Commercial Code

(i.e., § 2-615). Nor does this study make any claim to have captured all

the CCD cases that applied law from the Seventh or Ninth Circuits. In

other words, the study only focused on cases generated from states

within each of the circuits selected; the study, therefore, would not

have captured a New York court applying California law. That said,

5445, 2017 WL 5194914, at *1 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 9, 2017) (insurance settlement);

Koka v. Koka, No. B277116, 2017 WL 5898391, at *1 (Cal. Ct. App. Nov. 29, 2017)

(real property settlement agreement); Hensley for Hensley v. Haney-Turner, LLC,

No. Civ. S-01-2212, 2006 WL 8458651, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Sept. 28, 2006) (ADA

settlement).

97. The cases involving non-business transactions with adhesive contracts,

grouped by type, are as follows:

R

ESIDENTIAL

R

EAL

P

ROPERTY

T

RANSACTIONS

(10):

Prospect Enters., 2011 WL 2683004, at *1–2 (sale of townhome); Watson, 2011 WL

10069467 at *1–2 (residential lease); Archundia, 2009 WL 1796295, at *1 (residential

property foreclosure); Bean, 2012 WL 10349, at *1 (residential property foreclosure);

Reader, 2012 WL 125977, at *1 (residential property foreclosure); Gutierrez, 2012 WL

1033063, at *1 (home loan refinance and modification); Wear, 2013 WL 6008498, at *1

(residential home mortgage foreclosure); Deschaine, 2013 WL 6054456, at *1–2 (resi-

dential home mortgage); Bob Spain Real Est. Servs., 2015 WL 422371, at *1 (real

estate listing agreement); Balboa, 20115 WL 827064, at *1 (residential lease).

E

MPLOYMENT

-R

ELATED

T

RANSACTIONS

(2):

Dalkilic, 516 F. Supp. 2d at 1180–81 (Turkish interpreters during Iraq War); Dauod,

2010 WL 11595801, at *1 (forgivable loans repayable immediate if employee left

before 7 years).

M

ISCELLANEOUS